(2ND UPDATE) – Fidel Valdez Ramos, the country’s 12th president who, after defecting against his cousin that led to his ouster via People Power, envisioned a “Philippines 2000” only to be dashed by a financial crisis near his term’s end, died today due to complications of Covid-19. He was 94.

In a short statement tonight, his family confirmed his passing: “The Ramos family is profoundly saddened to announce the passing of former President Fidel Valdez Ramos. We thank you all for respecting our privacy, as the family takes some time to grieve together.”

Mr. Ramos, who graduated from West Point in 1950 and fought in the Korean War two years later, was the second chief executive of the Fifth Republic, established soon after Ferdinand Marcos Sr., his cousin, was toppled after his two-decade dictatorship. He was acting chief of staff of the Armed Forces at the time when he and Juan Ponce Enrile, then the defense minister, protested the widespread fraud during the 1986 snap elections.

When Corazon Aquino took the helm, Mr. Ramos was appointed defense secretary in 1988.

He would later run for the presidency, in 1992, as the administration standard-bearer under Lakas-Christian Muslim Democrats (Lakas-CMD), a party he founded after losing to Ramon Mitra as the nominee of Lakas ng Demokratikong Pilipino (LDP).

Mr. Ramos won by a sliver against Miriam Defensor-Santiago, garnering just 23 percent of the vote. Mrs. Santiago pointed to widespread outages as evidence that fraud occurred. “Miriam won in the election, but lost in the counting” was a famous tagline that reverberated after the campaign. The Supreme Court, acting as the Presidential Electoral Tribunal, dismissed her protest because she ran for senator in 1995.

Mr. Ramos, the first and only Protestant president, aimed for unity in his inauguration in 1992 at the Quirino Grandstand: “Some of us think that empowerment means solely the access of every citizen to rights and opportunities. I believe there is more to this democratic idea. Our ideology of Christian democracy, no less than its Muslim counterpart, tells us that power must flow to our neighborhoods, our communities, our groups, our sectors and our institutions – for it is by collective action that we will realize the highest of our hopes and dreams.”

“We cannot dream of development while our homes and factories are in darkness. Nor can we exhort enterprise to effort as long as government stands as a brake – and not as a spur – to progress,” he added.

His presidency was quickly tested by rolling blackouts, a sluggish economy and an emboldened armed insurgency.

Mr. Ramos called for Congress to establish the Energy Department, which would eventually give him special powers to expedite the building of power plants. He pioneered the Build-Operate-Transfer program, where private entities were invited to execute government projects and charge users afterward, an initiative that President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. now wants to amend as part of his 19 priority legislations.

The mid-1990s was an economic boom for the Philippines, dubbing it the “Tiger Cub Economy in Asia.” His five-point “Philippines 2000” program stabilized the stock market and skyrocketed the gross national product (GNP) to six percent in just two years.

“Philippines 2000,” likened to his U.S. counterpart’s “Bridge to the 21st Century” roadmap, was a tough program to be executed in a democratic country still mired in an oligarchic economy. But he said that it could be accomplished by invoking “the self-discipline of civic responsibility.”

“Authoritarianism eased the way to economic power and higher living standards for our East Asian neighbors. In contrast, we are working to reconcile our democratic politics with an oligarchic economy left over from the colonial period – not by changing the political system, but by democratizing the economy,” he said in his State of the Nation Address in 1993. “We Filipinos have always accepted that people with more are obliged to help people with less – in the name of a common, compassionate humanity. This traditional moral code we shall make a principle of public policy.”

Stability was a component of achieving “Philippines 2000”’s objective of modernization. Quelling insurgency and making peace with rebels and separatists were necessary steps to attain that.

Mr. Ramos scored a peace agreement with the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), led by Nur Misuari, in 1996 and outlawed the Anti-Subversion Law that paved for the legalization of being a member of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP).

“Today, we are all victors once again. We stand triumphant over war and violence – over fear and mistrust – over disunity and despair,” he said when the final agreement was signed on September 2, 1996.

In his first two years in office, opinionmakers felt that the country’s mood was “more upbeat” than ever before.

“The aura of hope that surrounds Mr. Ramos is not as brilliant as the spell [Ramon] Magsaysay wove, but his influence may last longer and be more substantial,” Robert Elegant wrote for the International Herald Tribune in 1994.

But the presidency isn’t all rainbows and unicorns, as his administration weathered major controversies.

Nearing the midterm elections, Mr. Ramos was confronted with the execution of Flor Contemplacion, a maid working in Singapore accused of killing another Filipino maid and a 4-year-old Singaporean boy.

Mrs. Contemplacion, 42, was brutally treated before her death on March 17, 1995. The court didn’t believe the testimonies of fellow Filipino maids proving her innocence, sparking widespread anger in the Philippines over a longtime economic partner.

Mr. Ramos pleaded to delay the execution, but his effort went nowhere. He recalled the Philippine ambassador to Singapore and endured the public’s anger, who felt that the government didn’t do enough to save Mrs. Contemplacion’s life.

“Today, the body of one such heroine is coming home, and I refer to the late Mrs. Flor Contemplacion,” he said at the time. “The death of your beloved Flor will not be in vain. It will spur everyone to recognize and uphold the dignity of the migrant worker who is the Philippines’ contribution to other countries’ development.”

In 1997, the Asian financial crisis dashed the country’s growing economy. The Philippine peso devalued to a whopping PhP42 against the dollar in 1998, a 61-percent increase from the previous year. In addition, businesses were closed and unemployment notched up in Mr. Ramos’s final years in office.

The Ramos administration’s denouement came about with his failed effort to revise the Constitution that would have allowed him to run for reelection. Mrs. Aquino, the Catholic Church and the general public pressured him to ditch this effort, which was done to keep his opponents off balance and avoid becoming a lame duck, according to his then-political adviser Alex Magno, now a columnist at The Philippine Star.

But his gamble to elevate his anointed successor, then-Speaker Jose De Venecia Jr., to the presidency failed. His vice president and then-de facto opposition leader, Joseph Estrada, ran a populist campaign to win by a landslide.

Born March 18, 1928, Mr. Ramos was born in Lingayen, Pangasinan, to Narciso Ramos, who would eventually become a foreign affairs secretary, and Angela Valdez, second-degree cousin to Mr. Marcos Sr.

A decade after graduating, he held several positions in the military, including the Presidential Assistant on Military Affairs in 1968, Chief of the Philippine Constabulary in 1972 and Director-General of the Philippine Integrated National Police in 1975.

Being an elder statesman, he was active in the nation’s intricate and, oftentimes, messy political affairs in his post-presidency. Mr. Ramos urged his successor, Mr. Estrada, to resign in 2001 after corruption allegations blew out in the open. And he endorsed Rodrigo Duterte for the presidency and Leni Robredo for the vice presidency in 2016.

“President Fidel Ramos, sir, salamat po sa tulong mo making me President,” Mr. Duterte’s opening salvo in his inaugural speech.

But as the drug war tarnished the human rights situation in the Philippines, Mr. Ramos began harshly criticizing the strongman, warning of a “culture of impunity” emerging out of Mr. Duterte’s cornerstone legacy.

“I think it is starting to become like that, although I don’t want to call it that because being a senior citizen, who had been through the experience and done it, I’d like those in command now starting with President Duterte down the line […] that hopefully based on the guidance from the very top, there could be positive change the way we do things in this country. I’m still hopeful about that,” he told Rappler in 2017.

His assessment of the Duterte administration in its 100 days wasn’t flattering: “In the overall assessment by this writer, we find our Team Philippines losing in the first 100 days of Du30’s administration – and losing badly. This is a huge disappointment and let-down to many of us.”

And he sharply rebuked the hasty burial of Mr. Marcos Sr. at the Heroes’ Cemetery in 2016, noting that it was an “insult” to the sacrifices of the Armed Forces.

“I felt very bad especially for the veterans, as well as the members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, as well as members of the PNP which I commanded then,” he said. “It was an insult, [a] trivialization of the sacrifices of our Armed Forces, PNP, Coast Guard, veterans – retired and active.”

He then underscored that his revolt was his atonement after leading a military that brutalized activists, oppositionists and advocates during Martial Law.

“My apology was more than an apology. In the Christian tradition, you confess and then you atone. My atonement was leading the military and the police during the EDSA People Power Revolution. From the 22nd to the 25th of February 1986 and I stand by that record. It’s there in history books,” he said.

Mr. Marcos Jr., in a series of tweets tonight, expressed his deepest condolences for the former president’s family: “I call on all Filipinos to pray for the eternal repose of Mr. Ramos. The legacy of his presidency will always be cherished and will be forever enshrined in the hearts of our grateful nation.”

Malacañang paid tribute to Mr. Ramos in a separate statement this afternoon. “He leaves behind a colorful legacy and a secure place in history for his participation in the great change of our country, both as a military officer and chief executive,” Press Secretary Trixie Cruz-Angeles said. “We deeply condole with his family, friends, classmates, and associates, and keep in our prayers.”

Vice President Sara Duterte, who co-chairs Lakas-CMD, underscored his achievement of bringing peace in Mindanao in signing the peace agreement with the MNLF: “He was a real patriot – one who encouraged men and women in uniform to value their integrity as public servants. May we find inspiration from FVR’s life and the immensity of the legacy that he built out of his love of country and fellow Filipinos.”

Mr. Estrada, shocked by Mr. Ramos’s death, described him as “one of the most effective presidents in our nation’s history.”

“[H]e brought to the presidency a different view of how problems should be dealt with, overcoming them in the most pragmatic, cost-effective, and fastest way,” the 13th president said.

Senate President Juan Miguel Zubiri mourned the passing of a “bright leader” always one step ahead: “Maybe it was his military background, but as a politician he was always able to quickly assess the landscape, and formulate the best way forward through consultation and consensus.”

And Deputy Speaker Ralph Recto called him “Steady Eddie” for steering the country towards economic development: “He was the Steady Eddie who led by infectious and inspiring example, from the trenches of Korea, to the corridors of Malacañang. Whether in the battlefield or in the bureaucracy, he was daring in deeds and bold in thinking.”

After his long public service, Mr. Ramos’s ascendance to the presidency was a feather in his cap, he said, adding that that stint was “a matter of destiny.”

“A person can plan or aspire to become one all his or her life, but ultimately, the confluence of many things — people, the current political milieu, events, chance, and the candidates’ personality — will bring the presidency to the Anointed One. Destiny,” he wrote in the foreword of “Behind the Red Pen” by Jojo Terencio, his close aide.

“So many things have happened since then but I have strong faith in the Filipino people, our leaders and the country’s future. We continue to aspire for a better life for all, and we will continue to work together to make it happen,” he added.

He ended his foreword with his famous catchphrase: “Kaya ba natin ito? Kayang-kaya basta tayo ay sama-sama!”

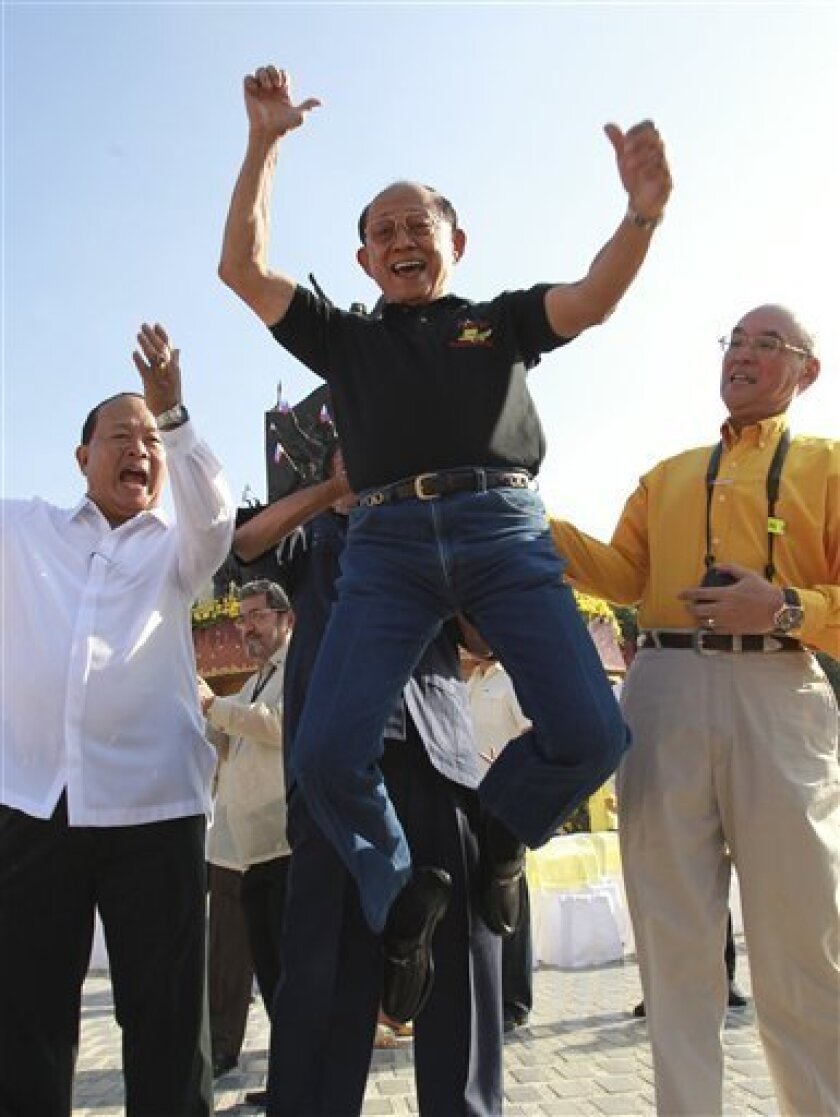

Featured image from The Times | Victor Harber.